She had come from afar. It was the first day. And she was walking through Solonga’s loft. In preparation. Swallows with last efforts last wills against the pain that wishes it to speak. Theresa speaking from afar through layers of cotton bandaged all around her throat. A growing spot growing red, more and more red as red as apple feeds its bleed of ghost. Must break. Must void. She allows others in place of herself. This is what this project has always been about. Admits others to make full. The weight of history. The others each occupying her. Make swarm over her flesh. Flesh up me in New York City. Midwifery and bitch me. Unstitch my salve and let me bleed. When the amplification stops there might be an echo. To see their names and hear their words. She waits inside the pause that is my life. This very moment here inside Solonga’s loft. The view of park. The children out the window playing. There will need to be a bloody bever. Thicker now even still there’s blood. Another layer. Weight the pain must say. Inside her voids is flesh. She takes. The pause. Slowly. It will fit you pretty well.

And she, who is also interested in history, is reading Dictée like the script of an avant-garde movie. The kind of film Theresa liked. Hoped to make one day. In longer form than anything. She’s tried. This book will come now this. This film. Inside its pages. Surface.

She sees Theresa’s book on Solonga’s shelves. The original edition. Dictée, published by the Tanam Press in 1982. And reads it. Learning later of her death. Learning later of her having been murdered. Learning later that she had also been raped. Weight scraping on wood to break the stillness of bells.

Cha’s use of the period Flat Beckett is so aggressive it flattens her voice into a hard robotic drill.

Driving forward and braking. And braking. And breaking. Every line. With a period.

The day of the funeral Textual objects her parents receive a copy of her book. She’d mailed it just a few days before.

She hands her ticket to the usher, and climbs three steps into the room. She proceeds to the front. Close to the screen. She takes the fourth seat from the left. The utmost center.

‘An Oriental Jane Doe,’ according to the police. Dumped in a parking lot on Elizabeth Street. Rub. Straw. Shaft. Near where she lived. No hat. No gloves. One boot.

Basement strangled and beaten. Belt around the broken hyoid of her neck.

Her friends toast her book in St. Mark’s window. Her scratch marks on his face. Her ring around his finger. Her gloves in that basement looked alive.

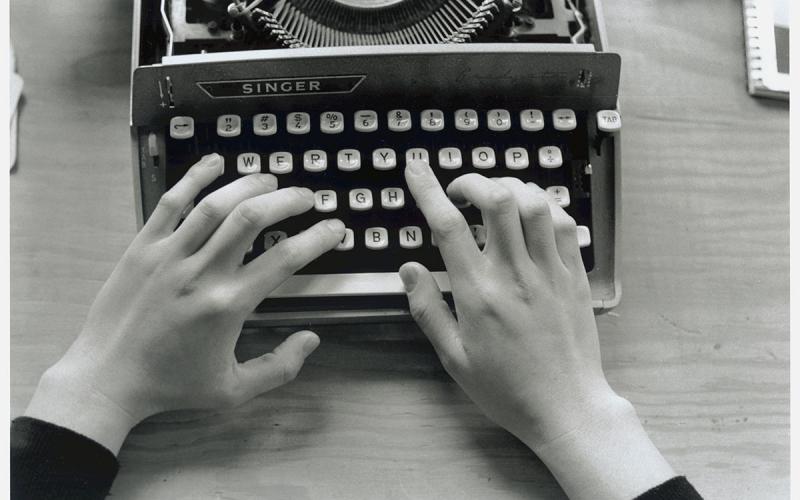

In Dictée, calling from the underworld. Her photographs of hands. Shown posthumously.

The burden of history. The Japanese repression. The Soviet oppression. The North Korean. South Korean. Recent past that is no more. The 1970s New York. French. Korean. English. Dutch. Dictée.

A way of saying more by speaking less. Her portrait seen by the movement of the camera as it pans to where she might be standing, might be reading, might be writing, might be going soon to sleep. You do not see her yet. For the moment, you see only traces.

She’d arrived two years earlier in 1980 to be a part of the conceptual art scene. But it is already dead. Now there are stars instead of artists. Schnabel. Salle. Clemente. That night she planned to watch a film by Straub-Huillet at the Public Theater.

She was to see it with two friends.

Meet Richard at 5 at the Puck.

She is interested in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s history and how it crosses with her own. The way Cha wound up in New York and never left.

It is a weave few readers care to look at with some care. The woven textures of Strzeminski’s Unist paintings. And time is now a part of the weave.

Cha works in textiles at the Metropolitan. She has a group of photographs of hands drawn from a variety of sources, from ancient Chinese prints to modern French paintings, cropped and reproduced, in various gestures.

To scribe. To make sounds. Make flesh. Dictée first. Anniversaries second. And then constructivism. Julius Eastman and Nasreen made Woodman. Wood. I would and will of course. To do. And meek eat flesh. Dictée before Apparatus. Follow the single line.

I find myself incapable of following a single line.

Move all the way to the right-hand side of the wall. An object painting made of scraps and wood and painted white. It was painted by Solonga. She constructed it in 1989. Beside it hangs a tiny photograph of hands by Cha, close to the wall in its tiny invisible frame. We think these might be Cha’s own hands, long and spidery her fingers paused in medias res and hovering before the keys of a Singer typewriter, as in her short film Permutations, where we think the face we see must be her own, so the hands might belong to someone else, her younger sister Bernadette. The line divides in two.

One step right from the desk. Follow the single line.

The sound instrument is made from two pieces of flat box-shaped wood, with a hinge at the center.

Two lines with space between. But if you were to weave them dense. Another other line. And so much else. For there is not a center. And all of it is full. Look at you here.

Banner and banter and not a lot of verse, reverse. White lilies and the daffodils that look at you whenever you go out. Each pew holds nine. So sit there quietly. The next verse. And then back to the first. Until it begins.

And it begins. Here. Again. From afar.

She is interested in the burden of history.

I write. If I am not writing, I am thinking of writing. I am composing. Documenting. Recording movements. Movements I record and also choreograph. That is writing. That is composing. Near black ink drawing a line over a pulpy sheet. Flooding what will come and stopping as the drought sets in. The dryness of the heat over the bones. Wet made fleshy and precise. But there is no sign of flow.

Something of the ink resembles Marta’s face. Others when possible. Scratch to imprint. She pushes hard the cotton square against the mark to make another book. One of Marta’s treated New York City guides. Apparatus as well. And a beam of light shoots out into the dark. Made filled. Sand. Its body’s extension of its containment.

The stain begins to absorb the material spilled on. And a line splits in three. Theresa, Marta, and myself. Collect the loss directly from the wound. Contents of the others seeping outward. I can hear the children laughing in the rain. The laughter dims. The commas and the periods. Ways of pausing. Being silent. Pages and pages. A little nearer. Advent.

Cha was not only a writer and a filmmaker and an artist, she was also an anthologist; although, of course, a good anthologist, someone who understands, who is sensitive to the gaps between texts, who composes speech as well as silence, is also, by necessity, an artist.

The medium or the mediums I will use depend on the requirements of any given work.

There was no firm distinction between Cha’s visual and linguistic practices.

In a 1981 summary of her work, Cha wrote that she had been working as a visual artist and writer since 1972.

To address and to incorporate the apparatus.

This year that I was born she was beginning. This book conceived as a collection. Autonomous works. A plural text. Revealing. Reveling in. Unraveling the process.

I hope this book in its totality.

She is interested in the burden of history. Apparatus. History as a movie projector. But without the speakers. History as a machine. But without the sound. It is a reading of gestures. Or so is one conception. Cinematic. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha coming to New York from San Francisco. She is editing a new anthology to be released by the Tanam Press in 1981. She reaches out to Straub-Huillet for something to include. She is interested in history. In language and the moving image. In words that can be sourced and made collage. In photographs and human gestures that can be made to work with symbols. She takes images and words and makes them dance across a screen. They are about her life and they exist but they do not point. They are a kind of mute dictation. Dictée