to the people of new york city

(a sketch in pieces)

Oak leaf never plane leaf

There’s a filling of the page

out from non-consecutive arrays

gathered feldspar phylotaxis

It was just an enormous amount

I think it covered everything

Words, spoken words, turning into sounds

Something to be gathered

Something to be arranged

Begin the story of arrangements

It was a matter of using his hands correctly

Altogether tactile, sensuous

An aggregate of unposed

image barest fact

The emphasis is on the stage

the connection between images on a page

page to page

self-portrait

spread Lay, as he lay there

on the floor strand and wide

wither

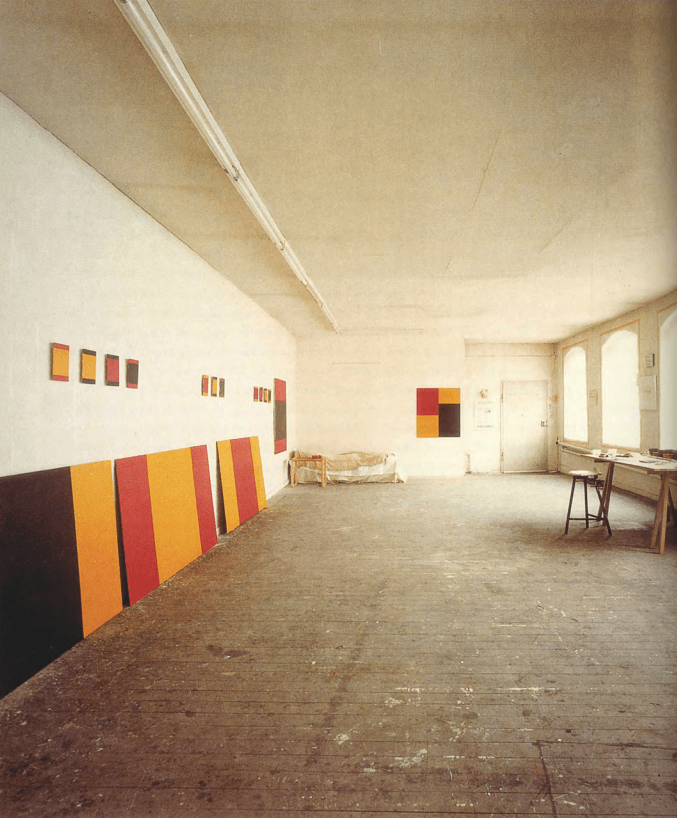

The rhetoric of interior spaces

She turned to me and said, “I feel

the air from other planets,” and was quiet

Taking his place behind the tape recorder,

he then began to speak

He began to record what he would write

to transcribe orally the accumulations of a life

A novel as “accumulations of a life”

in the form of notes

Blocks of copied text

Reflections evocations image

Sitting before the recorder he begins to speak

reading into it his notes

He’d be sitting by that little table with the shadeless lamp.

I was seeing him at the time, writing stories of my own, a poem published in Horizons, a sonnet published in Mist, a haiku in Channels, a sequential little thing that I’d been working on for years.

And he was living then on Mary Street.

Patterns on the floor brown and yellow

patched The wood is warped and the planks

A pattern of pipes behind the sink outlets switches lights

A tall glass pitcher filled with water

He would use the term “composition,” a word he revered, for work built up, layer after layer, over time, drawn in long procession from his notes.

“These contrapuntal unravelings, loomings,” he would say.

And all his life he preferred the vitally impure.

But experience cannot be thought or painted, only noted and composed.

He had these pieces lying all over the floor and he would pick them up.

It’s a movement into something more. Not really a poem, such is life.

As if without interference, without a teller someone to tell

The more you work, the less you exist. I am nobody.

My childhood bends beside me.

I feel the heaviness of this chair, the weight of that door, the play of light upon this sheet.

The uniform matteroffactness of a meandering male fist

But the blindness of the process “what might be” is not a ground

A tender red

Color laid indefined like stains

Bent on absorbing unfamiliar items into chalk

The black and white of printed words

Something turned something spread used to cover surface

A long dull poem and a bare one

Skirting reference extra words

A stool she likes to step on and a knife

“I caught a bird which made a ball.”

“I caught a ball which made a bird.”

It alters.

An encaustic line. Relief.

And why should I be so concerned with “sense” when there’s a window here. Rabid fellow tokens and a chest.

“Because the latest thing in art is just the latest thing in art.”

Slowly squatting.

I’m interested in grids. In typological structures. Juxtaposing things. And for this a book, a handmade book, is what makes sense. It’s what I need. Spending a lot of time with Benn and Hilde, I learned a lot from what they did, how they’d be putting things together, side by side or so to speak, although they worked primarily with sound, it’s much the same. A matter of structural relationships and chance.

His writing developed essentially as a way of sculpting. It is a patchwork, a weaving together, a convoluted account, hollowing out of sound, drawn mostly, a bewildering and bloody list, from life.

He wasn’t at all conceptual. He was poetic. He was literary. He was musical. And yes, he could be quiet. He loved to talk about music. He was very enthusiastic about music. Highly unusual music. The extreme innovations, which mostly come from America.

But one can talk him easily to bits. Instead, one should perceive his work all at once like a breath.

But I do in a sense mourn.

He loved black hookers. He loved Times Square. He loved Canal Street, Coney Island, people selling candy, wacky ethnic places, rides.

Notations in felt pen and pencil on blue paper used for mailing letters.

The particular characteristics of a given space.

Notes arranged on cardboard sheets.

Documentations, “conceptual instructions,” the impossible task of rescuing centered on an experience that can no longer be had, interview fragments.

I think he once referred to it as an unfolding.

A wall drawing with music.

A dark blue line following the contours of a door, a radiator, several windows.

“Unexpectedly complex,” he said. Aluminum panels. Chords of color. And lots of empty space.

A murmur in the wind.

I could have waited.

And the cycles of the day, the night. The cycles of the seasons, flying into town, the simultaneity of things, every time, in an immediate way, without preparation, between departure and return.

His first wife Ingrid and her daughter, Iris-Jasmin.

Thin strips of wood. Stretcher sides. A ballpoint pen on whitewashed reverse, following the arrows where they point.

Water scales, plum and trees, the changes in the light from cool to warm, red bricks and plants; all of this, of course, without transition, intimation.

I think he was a new person in New York. It absolutely woke him up to what he was. He was a little drunk. He was holding on to the table. His fingernails were dirty and I liked the way he looked. He asked me who I was, I said Babette. And I told him I could paint them. I said gold, and he said fine. He amused me, how he acted, like a child. He kept quite still throughout.

But he might as well be dead. It was a most unexpected illness. And his compositions by that time had been extending. A pencil pressed on paper, a red clothbound book. And against the pale blue rule, a scattering.

Smudges and tears bewildering leaves.

A simple statement of fact in a certain form. You sweat like a dog for that.

But what I required was an uninflected surface, something to resist my piddling hopes and burdens, something harsh.

Twenty-Four Short Pieces. It was a way of drawing out without extending time. A burst, you might say. It took me seven years.

To write, to scratch, to carve.

A constant series of events. The aim and acquisition of a non-descriptive line.

That which is already altered.

These assume their own reality.

But something always seems left out, somehow blurred, made invisible.

It is just here, but without revealing.

It is virulent and it breaks.

And something always happens.

A coming to life. A stroke. A line. Intervals.

An inconspicuous economy.

It is the moment of the snow itself.

A new beginning every time.

Moderating whiteness. Adding dirt.

Spreading the gray paint with our fingers. Brudie taught me that. We were learning to paint with our hands. Enjoying all the things that we could touch.

The shade and the light and the dark and the back.

Having to redeem.

Insolvent image. Break.

Pleading somehow for weight.

He decorated his studio with American adornments and collected ragtime music. He Anglicized his first name and cultivated an American persona, persuading not a few of his friends that he was half-American or at least had been to New York.

Shrink-wrapped, and obscure. Made intact somehow.

I think that color, the use of color . . . I didn’t particularly want to use or add. And every now and then I have a feeling. Sometimes it is a red, sometimes it is a yellow, sometimes it is . . . or a blue. But I did develop it in color . . . or a black perhaps, because of the color, quite particularly.

Color is collected in his drawings. Color is collected in his notes.

An unmarried woman Schwarze her name The father Stolle probably dead Adopted nearly at birth, a month coming on Peter a little bit taller, thinner than Michael never really recovered told at 18 from the shock Heisterkamp Wilhelm and Erika Leipzigians A year later quite unexpectedly a sister named Renate After marrying Kristin Kristin after Ingrid (both and with Babette a former child) living on the fourth floor of a school a former school in Dusseldorf But music remained at the core of his concerns.

He was obsessed with color, musical color.

He was all consumed with timbre.

He preferred doors, open doors. They always suited him. His paintings were like doors. Open doors sealed shut. He had a knack for closing down the possibilities, cancelling the options, one by one. I was one of those doors he liked to shut. But he arranged it so I wouldn’t close, not all the way, not tight. I stayed open for him. I remain open, even now. I’m like the groupings in his final panels, senseless when viewed in isolation, but seen together, as I move from wall to wall, somehow forming something, something that was always missing, a unity. A redacted composition. He has found a way to spread me out, to make me occupy a half a dozen rooms, left me hovering in front of the walls, barely casting any shadow. I refract the light, and yet I’m porous, open. And the colors he has chosen, he has made me German. And yet I remain, he remains, New York.

He wasn’t interested in conventional painting, easel painting.

He seems to have wanted to test how far he could go in eliminating variations from his hand.

They seemed to me like things he found in the street that he would cover over with some cloth, and then color.

The notations in his notebook show that this was done on purpose. It was the source, the first step.

cadmium yellow deep creamy white fields degreased rather than colder bluish loose and vivid bleeds pronounced dividing lines interspersed

Above the bed he hung a disc, slate gray, made of stone.

I could always respect that, that he could make something so quiet.

A blue triangle, a small black square.

It’s always the interval between two things that can’t be measured.

It was a much more severe aesthetic.

The writing fills the page as drawing would.

It was very New York.

It was at a party at the Lampersbergs, the night I first saw him, that I knew. He would do this to me. It was inevitable. It was bound to happen. Taking me home that evening I knew he’d fuck me. I knew that it was crude. That it would not be making love. I was a subject. I was like a subject. He would poke and finger me, he would feel me inside out till I was raw, and I would let him. Afterwards we went to Pat’s. And how he loved that New York coffee, that American coffee you could only find at 2am in the Village, in the East Village, with a scone. And the jazz. He loved the jazz. The jazz that Bob had put him up to, along with metal, learning to paint on metal, how to use aluminum, to make it hold the paint together, do the things you want to and behave.

He bought most of his aluminum panels cut to size in metal-wholesale stores on Canal Street.

U-channel bars permit the panels to be suspended.

Soldered aluminum U-channels that he then glued to the reverse with epoxy adhesive or contact cement.

He was a quiet man. He barely spoke, but when he looked at you . . . Isa introduced us by the piano, beside her little “Japanese” who’d only then just “finished,” done “a darling job.” It’s true, the way she played the Schonberg pieces—Six Little Pieces for the piano. I’ll never forget it. Porcelain faced—dressed in satin—she couldn’t have been more than twenty—Isadora’s “latest find”—her little prodigy from Julliard—those tiny little hands. And she was bearing down aggressively on all those keys. Mother always told me it was all in the fingers. It was all in the fingers. And it was. All the time she played, he sat across from me, the second row, eyes closed. It didn’t look like he was even breathing. On Kurumba, they would say, they say it happened on Kurumba, on the island of Kurumba, that he suffocated there. Heiner Friedrich used that word, it was a kind of animal that chokes, it was “a suffocation.” He could no longer breathe. They said he stopped breathing. So it was possible for him to really stop. I know now that it was possible. Yet it doesn’t make him go away. So what if he’s not breathing, he’s around me. He is spreading me around, from room to room. I’m in pieces. And I will not be put together. I cannot be put together. He’s designed it so that this could never happen. He has screwed me to the wall and left directions—piece after piece, proportionally spaced. This is how it has to happen. How it will always happen. And so I visit myself and I move on. Out into the cold and rain. I don’t even have an umbrella in my purse. I never thought to bring one. I could see it falling—lightning—through the panes. I’m not going anywhere. I’ll remain here till it stops, or the museum closes, or someone kicks me out. I come here everyday. I like to look at myself, like this. And he knew that I would. I’m sure of that. He knew that I would. I’m Osiris. And Blinky was an orphan. He told me that after the second year. We were in my loft on Mary Street. He had the window down—the frosted rectangle at the top of the frame, it was down. Open. And there were pigeons on the roof across the way, a blackened water tower Bernd and Hilla came to take a picture of one time. They’d had to climb the fire escape, plant the tripod on my roof and there’d been lots of scuffling shoes, puddles from the rain the night before. And the ceiling had been leaking since that night. Bernd and Hilla must have damaged it that time, I can see it from the bed. But Blinky only grinned. I laughed and said I’d been invaded by the Germans. Not by me, he said, I might be something else. Not by me. All I know is Joseph is my father, you’re my wife. But we’re not even married. You’re my wife. You’re my country. He took hold of both my hands, wrapping my fingers round the post, and without using his own he began to rub against me, pushing me against the frame, almost folding me into it bodily. The night I found out he was no one he could come inside. And he did. I am feeling him against my breast as I begin to write this down. It was a little kick but it was high. Already it’s demanding. I will give it what it wants. When the time comes I will give it what it wants. I will let it take what it wants, and I will not complain. He is close to me. He is closer now than when he breathed on my skin. That night after the Lampersbergs he breathed on me. And I remember, I could feel his breath. I feel it now.