from People Who Died Alone

Mieke was born in 1972 in Nijmegan.

When she was three years old she taught herself to read.

When she was six, her family moved to Wognun.

Mieke was a brilliant student, one, according to a classmate, who sucked up vast amounts of knowledge.

On her eighth birthday, she announced to her family that God did not exist.

She spent some time in South Africa where she got married and where she got divorced. She also went to India, and, according to the friend with whom she went, she fell in love with the works of Nasreen Mohamedi.

She admired the severity of the drawings, but she could also see the poetry behind the lines in every piece, especially the photographs, which Mohamedi kept private all her life; she never intended for people to see them, probably because, despite their formal qualities, and however abstract they may appear, they are in some way ‘about’ the world.

I once told a South African friend about the relationship I had had with my South African husband. I told him why we broke up and that I couldn’t deal with his disillusionment and that being disillusioned had broken him down and that I was another contribution to the collection of disillusions. He replied that it was the stupidest thing in life to be disillusioned because one shouldn’t have illusions in the first place. I felt upset.

Mieke’s death was not a tragedy. Her life was not meaningless. It was good.

She made the choice she thought she had to.

She was intrigued to read about Mohamedi’s experiments with sound.

Silence oasis in acoustic parks.

The way she liked to capture the noise of banal activities, such as the screwing up of a piece of paper or a knife being dropped on a stone floor.

Recently Mieke came across a passage from Nasreen’s diaries. A friend recalls that she was very moved. According to this friend, she said Nasreen’s death at the age of forty-five was not at all surprising, that if you added up the numbers it made sense.

These little human markings done in pencil, barely even present.

In late 1994, Mieke returned to the Netherlands. She had decided to study photography at the art academy at The Hague.

Wednesday she was wrapped in a shroud from her own clothes made by the friend with whom she traveled to India.

She spends her time mostly alone, and after high school takes up drawing, then photography. She is interested in all those people who we see around us every day who live and die alone. She observes them when she goes outside, sitting in parks on benches, eating at a restaurant, carrying a grungy tote bag filled with food and papers as they cross the street, a rucksack on their backs as they enter a museum or a gallery, sitting in the very last row of a cinema watching a movie, wearing clothes that is slightly worn out but somehow nice as they sit beside her at a theatre or a concert, sit and read the paper at the library or a bookstore, sit beside her on a plane, their eyes are sometimes closed and they will never talk.

With this series of photographs made between 1998 and 2001, Mieke Van de Voort allows us into the private lives of the recently deceased. Carried out in collaboration with Amsterdam social services, the project shows the interiors of apartments just as they were found by social workers who were researching the identity of people who had died without any known friends or relations. Within the context of a wider examination of the isolation and anonymity that affect city-dwellers, Van de Voort tries to preserve both a physical and a spiritual trace of people forgotten by the world, people who died in complete solitude.

When one looks at these images it is easy to think that they have resigned from society and given up on order and structure in their own lives as well. The rooms certainly don’t look like the inhabitants were expecting any visitors.

She’d been reading quite a lot of Uwe Johnson, even visiting his grave in Sheerness, taking photographs. She thought she would explore his work, get a feel for his life when he was living in New York, and maybe write an essay.

In early 2002 she moved to New York City, having managed, with the assistance of her close friend Geert, to sublet an artist’s loft on Mary Street.

She needed a break from her life in Amsterdam. She needed something else. A new start.

She was helping her friend curate a show in the Village.

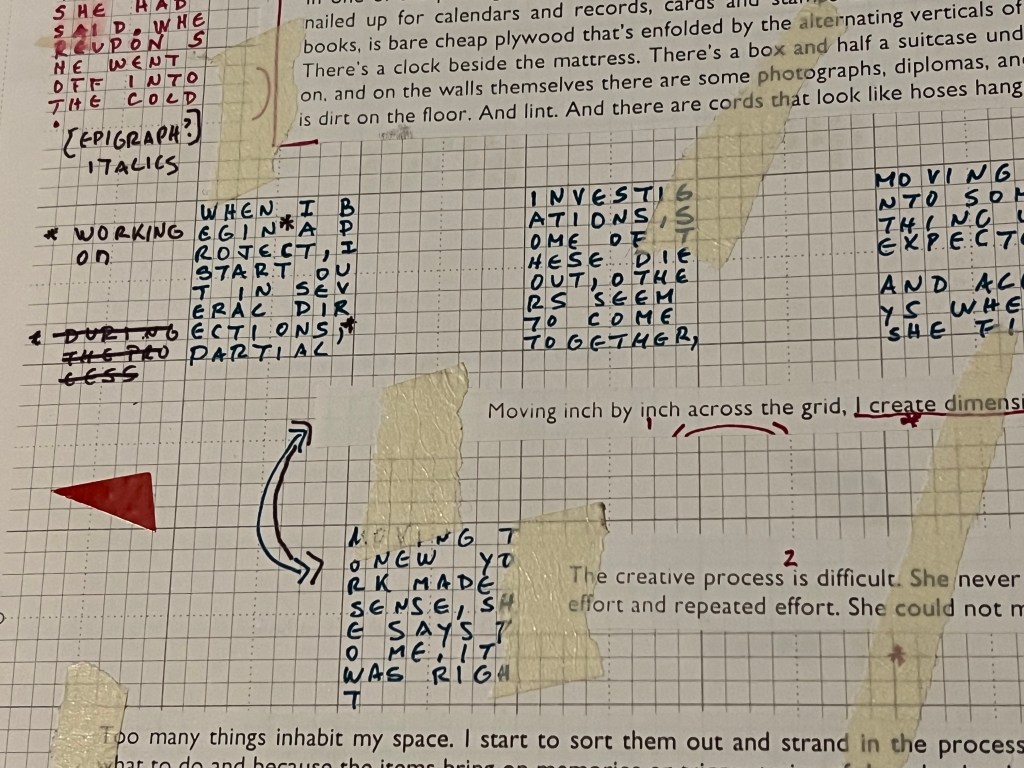

I create dimensions out of solitude.

No more than two on every wall. At least four and a half feet apart.

Out of these concentrated difficulties, drawings, calculations, frustrations and despair, one arrives at something very simple.

Her clothes, her beauty, her tightly braided hair.

None of the photographs sold, but I was told that they were very well received, that people would come back and they would sit or stand before them quietly and they would look.

Moving inch by inch across the grid.

This being so. And after nine and thirty years. Because I must.

Mieke ended her life a few days ago. Her father and her mother accept her decision.

But the panic attacks. She was already depressed. And what can one do? Psychiatrists give a pill and all creativity is slain.

I have a specific relationship with newspapers. I am never able to read them for more than a few days in a row. But I don’t throw them away because I think I might still read the bits that I didn’t cover and the ones I didn’t read at all because I am sure there are lots of interesting things inside. By the time the pile grows larger than myself and falls over, I start negotiating to get rid of it because I get tired of restoring the pile each time a tram comes by and not having read the papers and adding more to it. The passing of time is manifested in the pile and I don’t find reconciliation.

Most of the houses were quite messy, but the messes differed in quality. For example, many ‘pretty’ things such as tiny sculptures and paintings and furniture, nicely displayed but too many to be able to appreciate, gathering thick layers of dust.

After a long period, despair, but a kind of despair which is slowly reflected and finally, after long delays into the night, understood.

In one of the photographs, there is a wall, and hanging askew, between two large unshaded windows, the light caught streaming in, there is a cross, and on the table, there is a pair of unlaced boots.

Nine days earlier she ended her life. I read about the cremation in the newspaper. I was traveling by train. There were two other people in the car, a man and a woman, traveling by themselves, the man reading a book and every few minutes delivering himself of an enormous sigh. I began to think of it as something that was required of him, of a breath, something like a breath, much the way that pauses in a piece of music help enact its rhythm, while the woman sat stock-still throughout the trip and gazed outside. Occasionally she would move to smoke a cigarette or use the toilet, nothing else.

Some of the houses I photographed were almost empty. On the wall only a cut out newspaper photograph of the previous queen, nothing more personal than that.

She is already depressed. They fight each time that they go out. Things are not too good for them. He says he thought her smile was real. And there are the panic attacks, he doesn’t know what to do, not anymore, not like this, they are becoming much more frequent, how he should attempt to handle them. Usually he just leaves and sees his friends until she’s calm, back on the drugs the doctor says she needs. He adds, she has her camera. She can look at things. This must be a help, being an artist must be a help, I think it must be a help. It must be grounding, though I wouldn’t know myself, of course, he says, that’s not my thing. But we both care about the world. We have that.

She is staying in Solonga’s loft. Solonga’s table all in white – white painted wood (it might be larch). I sit here and I try to write. Her work, from what I see: Black Mountainesque constructions made of wood and paper and of trash. But clean, austere and white (she paints them white).

This is to be a sort of diary or book of notes (a window molded out of blood) from my time, when I was living in New York.

A small table is covered with beads – small brown ovoids, spotty against the black – over by the window, a translucent curtain blown, hovering as light in gentle slants, it breaks over the floor piled high with stacks, mostly newspapers, either collapsing or collapsed beside a small metallic bed frame with a mattress pushed haphazardly against the wall and several books. The sheets are crumpled and dirty. A camera can be seen to peer among the folds. The ceiling has been painted white.

Too many things inhabit my space. I start to sort them out and strand in the process because I can’t decide on what to do and because the items bring on memories and trigger trains of thought that I can’t stop.

But I forget what I was doing. So many unfinished stories, where is the beginning, where are my plans? The mess inside me multiplies the mess inside my head. I forget who I am. How did these things enter my house? Who was I when I brought them in? How did I become so fragmented?

In the bedroom, I found a walkie-talkie on a blackened pillow, half-finished paintings and a half-empty bottle of milk.

I used to have a friend long ago who only possessed as many things as she could carry by herself.

I once read an excerpt of a novel, I think it was by Paul Auster, where the protagonist creates structure in daily life by organizing things in terms of color. For example: Monday’s dinner: only green foods. Tuesdays dinner: only orange, etc. Limiting choice by color.

And there are the colors in my photographs. The blue carpet with the subtle patterns. The beige curtain. The white of the radiator darkened by a shadow that’s been cast. And the light. There is always the light. Except for all those rooms where the books are kept in cases and the blinds are always shut.

In one of the photographs there is a mattress pushed against the wall and some of it below the warping board nailed up for calendars and records, cards and stamps and boxes, little folders, cut out squares of newsprint, books, is bare cheap plywood that’s enfolded by the alternating verticals of beige and white that paper all the walls. There’s a clock beside the mattress. There’s a box and half a suitcase underneath the metal slab the mattress sits on, and on the walls themselves there are some photographs, diplomas, and some hooks. The bed is a mess. There is dirt on the floor. And lint. And there are cords that look like hoses hanging from some pipes.

The creative process is difficult. She never thought it was good enough. She complained about the blocks. It is also effort and repeated effort. She could not make something and then enjoy the whole process of its creation.

In one of the houses I found a note on the wall, saying:

and when I am dead

don’t be sad

for I am not really dead

you should know

it is only my body

that I left behind

dead I am only

when you have forgotten me.

I wondered if anyone else but him had ever read that note and if there was anyone to make sure that he wasn’t really dead.